Here are a few photos from our time here in Niue.

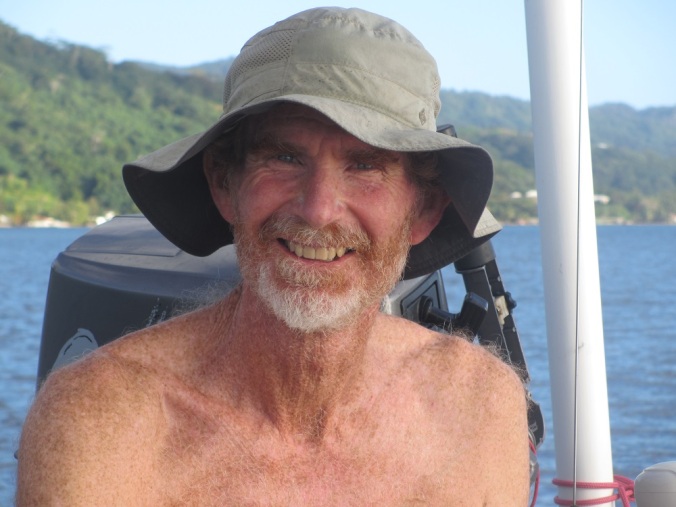

Anson

Here are a few photos from our time here in Niue.

Anson

Once again we traveled through geological time, for Niue was once an atoll similar to the idyllic Tuamotos, but now it sits as a rock in the midst of a vast ocean. For instead of continuing the slow journey into deeper waters, Niue was uplifted so that her thriving coral reefs were launched far above the sea. The coral animal life died, along with the algae that dyes it rainbow hues, leaving behind the imprints of life in bleached out limestone. Having snorkeled the reefs and passes of the Tuamotus, and having imprinted the shapes and textures of diverse coral formations in our memory, we simply shifted our gaze and added flesh to the skeletal remains of coral gardens, painting an image of their thriving underwater past.

Away from the shore, tenacious seeds grew roots in this hostile environment, and their decaying remains paved the way for all subsequent plant life. After thousands of years of this process, the soil is still a shallow layer atop the limestone base; tree roots lie partly embedded, the top half boldly rising above the life-giving soil. Many plants grow directly out of ancient coral heads, their roots anchored inside the caverns and holes. No rivers course through this rock island, and the thin layer of top soil is held firmly in place by intertwined roots of trees, ferns, vines, shrubs and grasses. All rain run-off is filtered through limestone crevices before washing to sea, creating a crystal clear meeting of ocean and land. In contrast, the waters around the Marquesas, rich with soil, covered in waterfalls, streams and rivers, became muddy pools with each downpour. Even the coral sand of the Tuamotus, aided by the disruption from pearl farming, and when churned by seas washing over the outer reef and strong trade wind blows, would mix with the ocean water, reducing visibility from 60 feet to a murky 30. Here in Niue we sit in 120 feet and can see the ocean floor.

The main attractions of Niue are along the edges of the island where processes of uplift and erosion interact to create magical enclaves, hidden pools, caves, caverns and chasms. We rented a van and followed the “Key Attractions” pamphlet from the Visitor’s Center, each site paired with a tantalizing photo urging us forward. Crossing the island to our first cavern, we journeyed through the Huvalu Forest Conservation Area, within which villages continue their customary farming practices. All signage in this region referenced sustainable land management, sustainable communities and customary rights. Taro fields, papaya, coconut groves, banana and pineapple emerged within clearings in the forest, with the slashed shrubs and branches serving as mulch to sustain the crops. Behind were younger trees with old growth forest framing the background.

Popping out of the trees we found ourselves on the east coast of the island, at the town of Liku. Had another cruising couple not shown me photos of the “road” to Tautu, we would never have found this site. Their directions were to spot the church with a stone wall in the shape of the bow of a boat and then drive across the expanse of green grass to find the car tracks to the hiking trail (‘track’ in NZ English). It was hard to drive by that church over pristine looking grass, especially since it was Sunday and people here are serious about church. No stores are open, and no immodest clothing is allowed in sight of a church, but with no prohibition against driving in front of one, across we went and stumbled upon a road.

The track wound down through a limestone cavern, and it was Anson who remembered that the stalactites hang down and the stalagmites grow up. This dripping limestone smoothed out the sharp remnants of coral, so we could climb and explore the caves without being poked and sliced. Devon clambered around, exploring the crevices, poking his head through holes that fish once swam through. Down below, the ocean waves crashed against the shore. Knowing we only had one day to explore the island, we hiked back up the path, through the dripping limestone and packed ourselves in the rental van.

We drove around the north side of the island, passing historic sites where Christianity was introduced in 1846 (by a Niuean who had been converted in Samoa and returned to save souls; this required an armed guard of over 60 Niuean fighters, as the gospel wasn’t universally welcomed) and where in 1863 a Chilean boat enslaved 109 young men to work in the guano mines of Chile. Our presence here is yet another intertwining of always, already intertwined worlds, hopefully one which is more life-sustaining for all involved!

Our next stop was Avaiki Cave on the northwestern shore, a low tide destination, and the site where the first canoe landed on the island. Hiking down this path we emerged on a coral plateau where water barely covered the bleached remains of a deep water garden. To the north a large cavern framed a shallow pool, with live coral tenaciously reproducing in the crystal waters. Brightly colored algae covered the walls of the cavern, reminding us of Painted Cave on Santa Cruz Island. Across the coral shelf, towards the breaking ocean waves, deep pools enticed us for a snorkel. Entering was easy: we found a spot of bleached coral to stand on and jumped over the edge. We swam like tuna, exploring the edges of the pool, following the fish that make these pools their home, and reveling in the live coral and its color giving algae, while sadly noting the profusion of bleached coral in these warm waters. The second pool we entered was slightly larger, and it was here we first swam with the beautiful ringed sea kraits (a type of sea snake). These curious creatures swim up from the depths, seemingly taking stock of each newcomer to its neighborhood, then turn and swim back down, their lithe bodies twisting gracefully in small curves towards tiny limestone caves. (Two varieties of crates live here: an endemic one whose bands are variously spaced and a species common throughout the region with evenly spaced bands of white on a bluish black body.) If only our exit was so simple! Clambering out of the pool, framed by live and dead coral, proved a bit tricky. Devon slipped and tumbled back in, but fortunately his slices weren’t deep, although painful. The dead coral spots provided poky toe and hand holds, which ultimately served their purpose, but we relied on those on land to exchange fins for flip flops. Ideally we wouldn’t have been wandering around this fragile ecosystem. For even those of us who can identify live from dead coral, and who care to avoid that which is living, knowing it takes decades to regrow, probably are doing harm inadvertently. (If, like us, people have a hard time staying away from such beauty, ideally a raised walkway with ladders into the pools would be erected to minimize the harm.)

Our next spot was Limu pools, just north of Avaiki. This track was popular with New Zealand tourists of a certain age. Doughy bodies lounged under the sail-shaped canvas erected for shade, while others swam languorously in the pools, as if at a hotel. We journeyed beyond and over a steep incline to find ourselves alone at another pool, fed by fresh water on one end and salt water from the waves pouring through the ocean pass on the other. Entering the pool we were shocked by the cold water, and swimming quickly towards the ocean edge, we found ourselves looking through our masks as if through old, wavy glass. A lens of cold, fresh water lay over the warm, salty ocean waters which drifted like long, clear tendrils below, not mixing until churned by the waves at the pass on the far end. We dove down and were immediately rewarded with soothing warm waters and a clear view of butterfly scythes, sergeant majors, box fish, parrot fish, and sea kraits. Here we swam under a limestone arch and explored until the cold drove us back to shore. Upon our return to the first pools, we joined the crowd (of 8) and explored the more accessible waters. These were warmer and gentler, and it was only our tight schedule that sent us scurrying out and up the path to the van.

A fellow cruiser, Dan, a singlehander from Kirkland, WA (yup, Costco’s home), joined us on this outing. By this time most of us were getting a bit tired, although Dan seemed ready to hike the 30 minute trail to view the Talava Arches. With Devon’s cuts preventing a hike we proceeded down the short track for a view of the Matapa Chasm. Here the ancient coral faces rise straight up for 100 feet on both sides, framing a narrow pool which was once the bathing site for Niue’s royalty. If this had been our first stop we would have donned fins, mask and snorkel and explored its length and depths. Instead we tested the water with our toes, declared it cold, and decided to retreat for a snack at the whale overlook. It was clear that more than food was needed, so we drove to one of the few establishments open on a Sunday for caffeine. Even after re-feuling we admitted defeat and realized we didn’t have the energy or time to tour the sites on the southern half of the island. So back to our boats we returned, feeling endlessly fortunate to have landed upon this magical island of Niue. Kim

After ten days at sea we arrived at Niue, our lines now secured to a mooring ball anchored firmly in the rocky bottom 80 feet down. There is no protected harbor on this island nation, only an open roadstead with the island between us and the Easterly tradewinds and seas, so Mark rigged our flopper-stopper device (a stainless steel plate with hinged wings) to dampen the rock and roll from the gentle but insistent swell. Land never looked so sweet to us as it did upon our arrival at dawn yesterday morning. And when we finally placed our feet upon the ground (after using a mechanical hoist to lift the dinghy eight feet out of the water and onto a dinghy cart for parallel parking on the wharf), and we let our bodies feel the unmoving earth, we were giddy.

This passage was hard. It was work. It built our skills and deepened our knowledge of our boat and of our tactics. It was also team work that got us here safely with no damage to our boat or bodies. One core member of the team, my father (Peter, aka Papa), sat in front of a computer screen in Monterey, endlessly analyzing the weather systems that made our journey so challenging, and sending us emails with updates that we snagged with our SSB radio.

We’re in a part of Oceania now where the persistent highs and lows spinning off of Australia and New Zealand below us interact with the South Pacific Convergence Zone above us. A high, high pressure system can push the pressure gradients together, causing reinforced Easterly tradewinds. That dynamic brought us the persistent 20 knot winds, becoming 25 knots, that were a daily part of our passage. Strong winds with long fetch built the seas into two to three meter powerful hills which chased us and tossed us about, occasionally combining their force with ours into an adrenaline rush of a surf down a steep face. Unlike our passage from Mexico to the Marquesas, where strong trade winds meant freedom from squalls (the powerful breeze blew off the tops of any localized low pressure cloud formations, and prevented the associated conduction of moisture into tall cumulous clouds which, if formed, unleashed their water weight with a fury), the SPCZ provided plenty of moisture in the air to deliver 30 to 32 knot gusts and rainy downbursts, any time of day, but especially on my watch of 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. So we were constantly on squall watch, reefing and unfurling sails, adjusting the wind pilot, and working hard to keep the boat moving safely forward. No sitting back and soaking up the stars and watching the moon rise; instead we peered into the dark night to judge the shape and texture of clouds, looking for hard lines which spelled strong gusts and a soaking, or breathing easily when we could distinguish a fluffy edge, knowing a sprinkle was coming, but without the fury of the wind.

But the reinforced trade winds were not our real worry, for this time around the high was not so high as to cause a gale of 40 knot winds. It was the lows that plagued us. The first low we weathered kept us in the Leeward Islands, shifting the winds around so that we beat from Raiatea to Bora Bora, rather than enjoying the usual downhill run from island to island. But the wind wasn’t strong yet, and the seas mellow, so Anthea was in her element, designed as she was to race sharply to weather. We reveled as always in her ability to point high without losing ground, often seeming to shimmy upwind rather than slip down from dreaded leeway. It was only when we turned dead into the wind and had to tack against a knot current, that we clawed, rather than flew, up the coast of Bora Bora and through the pass into the protection of the lagoon.

One night at Bora Bora was plenty for us to soak in the beauty of the volcanic peak towering over the lagoon, so we set out for Maupiti, only 30 nautical miles away, where we planned to wait out the quickly approaching trough of low pressure. Once out in the two meter seas, and after re-reading the sailing directions for navigating the long, narrow pass, we realized we could get into the lagoon, but barely. The seas, however, were growing, and we could get trapped inside a small lagoon for a week while waiting for the swell to diminish. So back we turned to the protected anchorage in Bora Bora, retreating inside the pass and treating ourselves to a glorious downwind sail to the southern edge of the navigable areas of the lagoon, before turning north and beating upwind with full sail in 16-18 knots apparent on flat water. We had the soundtrack from Mama Mia blasting out of our waterproof speaker, and I danced at the helm (to the dismay of Anson and Devon), stopping my disco moves as we approached land, so no stranger could witness the mortifying sight. It was a dream sail into a dreamscape of an anchorage behind Bora Bora’s signature tombstone peak. That night and the next we watched the full moon rise over the peak and waited for the low pressure system to pass on by. We hunkered below during the rain and checked to make sure the anchor held as the wind clocked around and re-established its easterly flow. Our anchorage was a bit rocky, but well protected, and our Rocna anchor held us firmly throughout. We left on the back end of the system, happy to launch the next phase in our journey.

The confused seas that made the beginning of the voyage so challenging below (recall Extreme Baking) were the mess left behind from that trough of low pressure. Five days into the journey it became apparent that another trough was coming right for us, with Niue predicted to receive punishing wind and rains. Our weather data accessed via the SSB showed black swatches of extreme rain and predictions of sustained 30 knot winds surrounding our destination; Papa’s resesarch showed more fine grained analysis with predictions of two inches of rain per hour in the worst spots. Evasive action was required. Papa searched for a safe spot for us to wait out the system, and we altered course to head north, tried to slow the boat down so we wouldn’t get there too quickly, but found the motion intolerable. We powered back up and arrived at our safe location, several hundred nautical miles northeast of Niue, well before our planned time. Our task: park the boat for 24 to 48 hours while the trough flowed southeast of Niue. Just lying ahull was one option, but that put us beam to the waves. Yuk! Forereaching under jib alone was also too sloppy. So up went the triple reefed main and out went a scrap of jib, which we promptly backwinded to heave-to. We crept along at 1 to 1.5 knots, heading northwest, and then tacked 18 hours later to stay east of the line of ominous weather.

Below decks the motion was tolerable, but just barely. Now standing watch meant a quick glance around for other boats every fifteen minutes or so. Party time! We broke out the chocolate covered biscottis, set up the movie screen, and watched the last two Harry Potter films with only a break for dinner. Standing watch that night was easy, but staying awake wasn’t since I missed my nap between dinner and 11 p.m. The next morning I awoke late, checked the weather and scoured the GRIB files for any possibility of setting sail. I saw a route that would have us sail only through grey areas (light rain), but this was tricky business and serious weather, so I called my parents for a weather consult. Together we confirmed that the trough moved faster than expected and a window of opportunity presented itself, but bad news also followed: that journey would take us into a dead zone of no wind as a high pressure system filled behind the trough. Yet 24 hours of sailing would put us within motoring range if we were desperate, so we loosed the jib sheet, unfurled the sail and set out across the lumpy seas and still strong wind and headed for Niue.

We were counting down the miles and making good time. The squalls weren’t more breezy, but lightning lit up the sky, with horizontal pulses every few seconds throughout the night. We were blissfully outside the center of the most intense weather cells, but Mark’s early morning watch took us through a three hour long thunderstorm with heavy rain and strong, shifty winds. The lightning was worrisome, but never dangerously close. We dodged the worst of it. Twenty four hours were up and the barometer still read less than 1013 mb– good news as 1015 mb meant no wind. Every hour sailing felt like a gift. Blessed be the weather dieties, for they pushed that high away from our route and gave us a sweet breeze all the way into Niue!

Once safely moored we heard from other cruisers who made different choices. One couple stayed on course to Niue and faced sustained 30 knot winds with gusts to 40 knots and 4 to 5 meter seas. Fortunately, they sustained no damage. Other folks already at Niue braved the moorings in a westerly wind and swell; a dreadful night on the mooring balls led to the loss of one dinghy when the sustained bashing ripped the attachment ring from the hull (serious business as there are no replacement dinghies between here and New Zealand), and a sleepless night as the reef was only seconds away if a mooring broke loose. That led the woman of one couple to spend the night in a hotel rather than stay aboard for a white knuckle night. Smart decision, as anyone who thinks they can save a boat from crashing on a reef with only a few seconds to react is fooling themselves.

Papa’s magic parking spot kept us in conditions that were relatively benign and nothing more than we face when we sail down the California coast. Thank you Papa and Nana for altering your daily plans so that you could be weather router par excellence!

The passage behind us, a treasure trove of adventures awaits. Tonight we go to a presentation on the humpback whales and the ongoing research based in Niue, followed by a preview of a National Geographic special on the island. Sunday we tour Niue by rental car (alas, no public transport here) to visit the numerous limestone caves and caverns, as well as the national forest which sensibly integrates people’s subsistence strategies into the management plan. And then there’s whale watching, snorkeling in crystal clear water, and the joys of cafes and restaurants (including an Indian restaurant run by a Punjabi family with whom we spoke Hindi with only a bit of French creeping in at the edges – our brain seems to have only one track for languages other than English). We’ll also enjoy internet, where we can read your comments that are otherwise not visible to us at sea, post some photos, bandwith permitting, and perhaps, if we are brave enough, read the news of the rest of the world that we’re blissfully oblivious to while at sea. Needless to say, we’re staying as long as the weather allows!

I have finally reached decent internet here in Niue of all places so here are some photos that have not been uploaded.

Anson

August 17 A Passage for Grieving

I’ve cried a lot on this passage, perhaps more than at any other time in my life. This is because there’s a reasonably good chance I won’t ever hug my mother again. About 3 ½ weeks ago I fell and severely cut my leg. Earlier that very same day my mother fell and broke her leg – for the third time. The first was a skiing accident at Badger Pass long ago. The second was a tobogganing accident below Mendocino Pass 10-15 years ago. This time it was while walking to greet a visitor at her door, just days before her 92nd birthday. My injury has subsequently healed, only a maturing scar – my Papeete tatoo, as Kim refers to it – remains. My mother, on the other hand, underwent surgery and a few days later returned to her home. She has excellent round the clock caregivers, is surrounded by family and friends, and is happy to be back in her own home. However, she has stated that she is ready to let go and depart this world. She lies comfortably (I believe) in a hospital bed and it doesn’t seem that she will regain mobility this time.

Most often I cry after one of our daily 6-8 minute conversations. It is so wonderful to be able to hear her voice and her chuckle, and to respond to her enduring interest in what we’re doing – Where are you? How are the boys? How’s the weather? What are you going to do when you get there?. Recently, we chatted about her memories of watching the Queen of Tonga ride in a horse-drawn carriage in front of St. George’s Hospital (where my mother trained as a nurse in post-war London), as part of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation procession. My mother noted that the Queen of Tonga had an enormous smile, and that they had a good viewing spot as Buckingham Palace was “just down the road” from the hospital. We also chatted about a stormy race around Santa Barbara Island in my parents’ Anthea (a classic 1926 wooden sloop) in which most other boats turned back due to the stormy weather but my mother and father continued on, rounded the island during the night and returned safely, even though the wooden seams had worked in the weather, allowing water into the boat. She doesn’t remember how they got the water out – details, details. On these calls we always tell each other how much we love each other. My mother usually mentions how she looks forward to my call, and today she said she treasures them. They come to an end after 6 or 8 minutes when she says, “Mark, I’m going to have to let you go now,” (which I think means that’s all the energy she has for talking). I cry afterwards because our brief conversation reminds me how much I love her, of how impossible it is to imagine the world without her in it, and that there’s a good chance I’ll never see her, hug her, again.

These cries are part of my grieving process, a process that began quite a while ago. At various junctures in the past few years, usually around a health issue that she might not recover from, I’d be sitting with her on sofa, blubbering about how much I loved her and would miss her when she’s no longer with us. During these conversations she’d often say something to the effect of, “well you know Mark, I’ve got to die sometime,” quite matter of factly. And that’s our mother – brave, adventurous, courageous and matter of fact. The grieving process also has entailed saying what needed saying. We have frequently acknowledged our love for each other, more frequently in recent years, perhaps as part of this process. Often, when returning to her apartment after dinner and a few hands of bridge at our house, she’d pause then say how proud she was of me and my family and how much she loved us. The tears that often came with these sentiments suggested she was making sure she said the things she wanted to while she still could.

We’ve been at sea 10 days now. For 10 days all we’ve seen is the sea, the sky, the clouds, the stars and the sun. Save for a few birds, there have been no signs of life. Our wake, our only trace, vanishes in seconds. Is this not a manifestation of eternity? Of the vast, perhaps uncaring, universe, in whose presence our lives matter little? I’m reminded of Virginia Wolf’s husband (whose name escapes me) who was fond of the adage, “Nothing matters, yet everything matters.” From the perspective of eternity, from the perspective of this watery world, it’s easy to agree that nothing matters. Yet after each call with my mother, the intensity and depth of my love for her, how precious she is to me, the ways in she has been a bedrock of support for me for over half a century, and the difficulty of imagining the world without her in it, overwhelm me and I cry tears of sadness. Yes, there is simultaneously eternity and deep grief.

My boys know the situation. They know Grandma has limited time. They’ve seen my tears. Kim has been wonderful, supportive, loving and compassionate during these sad days. Of course, there is much to celebrate as my mother approaches her final transition. Getting to 92 is “nothing to shake a stick at,” as she might say, and her mind remains sharp as a tack. She has led a truly remarkable life, as those who know her can attest. And while this is most unlikely, there’s a slight chance that we might celebrate an early Christmas with her and make her another batch of three citrus marmalade. Regardless of the timing of her passing, this crossing has been a passage for grieving. It has provided a unique opportunity to allow the tears and sadness to flow through me as I continue to come to terms with the certainty of my mother’s passing in the not too distant future.